It being Christmas time and all,

I’d been looking forward to indulging one of my personal holiday traditions: whipping

up a bowl of wassail and rereading Dickens’ Oliver Twist. After all,

there’s something decidedly Christmas-y about any tale in which a destitute orphan

rises through ranks of urchin pickpockets, endures poverty, depravity and exploitation

only to get everything he wants—a mom and dad and free room and board. This year, I

thought it might build some character to put a new spin on the annual ritual and get a

more authentic feel for what goes on in the book. Yes, this year I would become

Twist and try to see the world from his point of view, bruises and all. Instead of picking

pockets and artful dodging, though, I grabbed a flaming bowl of plum pudding and sat down

with Thief: The Dark Project, Eidos’ latest action title. Of course, it became

clear from the very start that this game had little in common with Twist. Indeed,

while the world depicted in Thief is as creepy and sinister as anything Dickens

cooked up for Fagin’s den of thieves, there is nothing sentimental about it. Then

again, I don’t think Dickens intended to offer his audience the Victorian-era

equivalent of one of the best written, looking and sounding multimedia action

gaming experiences ever released. It being Christmas time and all,

I’d been looking forward to indulging one of my personal holiday traditions: whipping

up a bowl of wassail and rereading Dickens’ Oliver Twist. After all,

there’s something decidedly Christmas-y about any tale in which a destitute orphan

rises through ranks of urchin pickpockets, endures poverty, depravity and exploitation

only to get everything he wants—a mom and dad and free room and board. This year, I

thought it might build some character to put a new spin on the annual ritual and get a

more authentic feel for what goes on in the book. Yes, this year I would become

Twist and try to see the world from his point of view, bruises and all. Instead of picking

pockets and artful dodging, though, I grabbed a flaming bowl of plum pudding and sat down

with Thief: The Dark Project, Eidos’ latest action title. Of course, it became

clear from the very start that this game had little in common with Twist. Indeed,

while the world depicted in Thief is as creepy and sinister as anything Dickens

cooked up for Fagin’s den of thieves, there is nothing sentimental about it. Then

again, I don’t think Dickens intended to offer his audience the Victorian-era

equivalent of one of the best written, looking and sounding multimedia action

gaming experiences ever released. First

of all, Thief--unlike most of the 3D shooters it might initially be mistaken

for--is not a shoot-‘em-up extravaganza featuring some anatomically ridiculous hero

who defies physics, the law of averages and karmic cycles while obliterating mutants,

techno-monstrosities and civilizations in his wake. In fact, Thief holds little

truck with games characterized by lots of noise and action, which isn’t to say that

it lacks these qualities. This game offers plenty of action, most of it of the

sweaty-palmed, hair-raising variety. Yet Thief demands that players exercise

stealth, silence and economy of action in order to proceed through the game. Players stand

a better chance of sticking around if they choose the surfaces upon which they walk,

proceed slowly, and stick to the shadows. In addition, Thief is one of the only

action titles I can think of which rewards players for patience and thoroughness and

encourages players to cover their tracks. So when players sneak up behind surly manor

guards or fanatical zealots and blackjack them, for instance, it is crucial to dump the

body--in a dark corner, behind a column, in the sewer--lest a passerby discover the crime

and start screaming, literally, bloody murder. First

of all, Thief--unlike most of the 3D shooters it might initially be mistaken

for--is not a shoot-‘em-up extravaganza featuring some anatomically ridiculous hero

who defies physics, the law of averages and karmic cycles while obliterating mutants,

techno-monstrosities and civilizations in his wake. In fact, Thief holds little

truck with games characterized by lots of noise and action, which isn’t to say that

it lacks these qualities. This game offers plenty of action, most of it of the

sweaty-palmed, hair-raising variety. Yet Thief demands that players exercise

stealth, silence and economy of action in order to proceed through the game. Players stand

a better chance of sticking around if they choose the surfaces upon which they walk,

proceed slowly, and stick to the shadows. In addition, Thief is one of the only

action titles I can think of which rewards players for patience and thoroughness and

encourages players to cover their tracks. So when players sneak up behind surly manor

guards or fanatical zealots and blackjack them, for instance, it is crucial to dump the

body--in a dark corner, behind a column, in the sewer--lest a passerby discover the crime

and start screaming, literally, bloody murder.

On the other hand, if players can make it through the

twelve missions by killing as few adversaries as possible, they stand better chances of

successfully fulfilling their directives; the expert level of the game requires players to

avoid physical contact with other characters at all costs. Players need to keep in mind,

too, that they have very limited health supplies--and the difficulty of procuring healing

potions lends this game a sometimes frustrating verisimilitude. The first few times I

played the game, I met my end several times because I was sloppy and left

evidence—open doors, knocked-over goblets and up-turned dishes, cadavers—in my

wake. When I finally got in the habit of erasing my trail, however, I was disappointed to

notice one of the only weaknesses of this game. Namely, after dumping a stiff into a

wooden chest and closing the lid, I was chagrined to spy the victim’s arms and legs

radiating from the container. It was as though the chest sprouted limbs; for a second, I

wasn’t sure if this werebox was a new species of villain to be blackjacked or not. As

it turned out, this situation was simply the first instance of clipping problems that

occur throughout Thief. On the other hand, if players can make it through the

twelve missions by killing as few adversaries as possible, they stand better chances of

successfully fulfilling their directives; the expert level of the game requires players to

avoid physical contact with other characters at all costs. Players need to keep in mind,

too, that they have very limited health supplies--and the difficulty of procuring healing

potions lends this game a sometimes frustrating verisimilitude. The first few times I

played the game, I met my end several times because I was sloppy and left

evidence—open doors, knocked-over goblets and up-turned dishes, cadavers—in my

wake. When I finally got in the habit of erasing my trail, however, I was disappointed to

notice one of the only weaknesses of this game. Namely, after dumping a stiff into a

wooden chest and closing the lid, I was chagrined to spy the victim’s arms and legs

radiating from the container. It was as though the chest sprouted limbs; for a second, I

wasn’t sure if this werebox was a new species of villain to be blackjacked or not. As

it turned out, this situation was simply the first instance of clipping problems that

occur throughout Thief.

In Thief, players assume the persona of Garrett, a petty

crime-committing street punk turned master thief who steals from the stinking rich

nobility and merchants of the City and gives the wealth he acquires to … himself. One

of the most entertaining aspects of this game is the protagonist’s cynical

personality, which emerges throughout play as Garrett offers his opinions on the

pretensions of the bourgeoisie, the frightening zealotry of the

religious-military-industrial complex (the Hammers), or the eerie supernatural currents

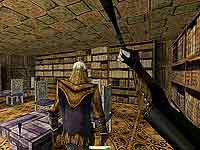

that run throughout the story (the Undead, the Leaf-man). Upon entering a book-lined

library in a lord’s manner, for example, Garret observes: "I wonder if he reads

them, or if they’re just there for show." This intermittent editorializing

enriches the game on many levels. It supports for players the illusion that the game

occurs in real time in a real place. It also reminds players of the larger narrative of

the spiritual war raging between the technologically puritanical Hammers and the chthonic

impulses manifested by the Leaf-man and his minions that frame Garrett’s adventures.

And finally, his voice sensitizes players to the sound of this game. At times, after

lurking in silence and listening for awhile, Garrett’s wry voice shatters a

player’s concentration to the extent that I often found myself running from or

ducking in shadows at the sound of this character’s speech. While unsettling, these

unexpected asides provide a sort of hilarious release. Indeed, in the end, it is Thief’s

sound that finally steals the show from Garrett. In Thief, players assume the persona of Garrett, a petty

crime-committing street punk turned master thief who steals from the stinking rich

nobility and merchants of the City and gives the wealth he acquires to … himself. One

of the most entertaining aspects of this game is the protagonist’s cynical

personality, which emerges throughout play as Garrett offers his opinions on the

pretensions of the bourgeoisie, the frightening zealotry of the

religious-military-industrial complex (the Hammers), or the eerie supernatural currents

that run throughout the story (the Undead, the Leaf-man). Upon entering a book-lined

library in a lord’s manner, for example, Garret observes: "I wonder if he reads

them, or if they’re just there for show." This intermittent editorializing

enriches the game on many levels. It supports for players the illusion that the game

occurs in real time in a real place. It also reminds players of the larger narrative of

the spiritual war raging between the technologically puritanical Hammers and the chthonic

impulses manifested by the Leaf-man and his minions that frame Garrett’s adventures.

And finally, his voice sensitizes players to the sound of this game. At times, after

lurking in silence and listening for awhile, Garrett’s wry voice shatters a

player’s concentration to the extent that I often found myself running from or

ducking in shadows at the sound of this character’s speech. While unsettling, these

unexpected asides provide a sort of hilarious release. Indeed, in the end, it is Thief’s

sound that finally steals the show from Garrett.

Thief’s sound will blow away everyone who plays it;

the way this game sounds stuns everyone I’ve forced to listen to it. Anyone who plays

video and computer games knows that sound and music can make a game either a maddeningly

mind-numbing exercise in repetition or a reality-warping immersive experience. Thief

belongs to the latter category. As players near the door of a city pub, drunken,

boisterous voices float from behind the windows; while ensconced in the darkened crawl

space of a tomb players can make out the plaintive moaning and halting shuffle of

flesh-eating zombies. For some mysterious reason, other characters nonchalantly whistle at

different moments in the game. While at times helpful precaution, it’s usually just

downright creepy.

What makes this game so sonically convincing?

Specifically, Looking Glass Studio’s 3D Dark Engine, an AI engine so sophisticated

that it can "hear" how players move on different surfaces and "see"

where they are in respect to light and shadow. A few players have complained that this

engine lacks the stunning visuals generated by the Quake 2 Engine. I would point out,

however, that Quake 2 and its imitators are much more visually oriented games; players

assess their progress through the game by blitzing through levels towards a cumulative

blowout. Thief, on the other hand, is not as linear. Not only do players have to

cover their tracks, they often have to backtrack to finish their missions, relying on

aural as well as visual clues to piece together the layout of a level or to get past

perilous situations. What makes this game so sonically convincing?

Specifically, Looking Glass Studio’s 3D Dark Engine, an AI engine so sophisticated

that it can "hear" how players move on different surfaces and "see"

where they are in respect to light and shadow. A few players have complained that this

engine lacks the stunning visuals generated by the Quake 2 Engine. I would point out,

however, that Quake 2 and its imitators are much more visually oriented games; players

assess their progress through the game by blitzing through levels towards a cumulative

blowout. Thief, on the other hand, is not as linear. Not only do players have to

cover their tracks, they often have to backtrack to finish their missions, relying on

aural as well as visual clues to piece together the layout of a level or to get past

perilous situations.

All in all, while some players may find that Thief

lacks the visual sophistication of other action/adventure games, it provides

players with a beautifully textured and well rendered world pleasing to the eye. The sound

in Thief, though, makes it amazing entertainment. I would buy this game for the

sound and story alone. How often do you get to be the wise-ass Everyman sticking it to the

oppressive establishment from the shadows? The fact that Thief also provides

players with challenging missions and is a blast to play leaves me begging, along with

young Oliver to Mr. Bumble: "Please, sir, I want some more!" -

--Greg Matthews |